In over 100 years of therapy, very little attention has been given to two elements of clinical practice: the body and positive emotions. Thankfully, somatic psychology and positive psychology have received increasing scientific recognition over the past two decades. This paper will explore ways in which somatics can contribute to the field of therapeutic healing, growth, and empowerment.

As humans, we are complex systems, which means that our functioning is organized through multifaceted and interdependent relationships. Through evolution, simple life on Earth manifested with a basic physiological structure, affect followed and culminating with cognitive capabilities. This evolutionary process grew out of a need to complexify adaptive responses to augment chances of survival. While cognitive analysis can be of great support to heal and grow, both the weight of physiological processes such as the nervous system and the strength of emotions and moods to influence behaviour provide important therapeutic routes for resiliency and empowerment.

Through its integrative approach to therapeutic conceptualization and practice, NeuroSystemics emphasize therapeutic interventions focusing on physiology, affect, cognition, and interpersonal dynamics. This paper will first briefly summarize the meta-developmental trajectory at the heart of NeuroSystemics’ conceptualization and range of therapeutic interventions. Second, a closer analysis of biological and affective dimensions of resiliency and empowerment will be described.

A meta-therapeutic methodology

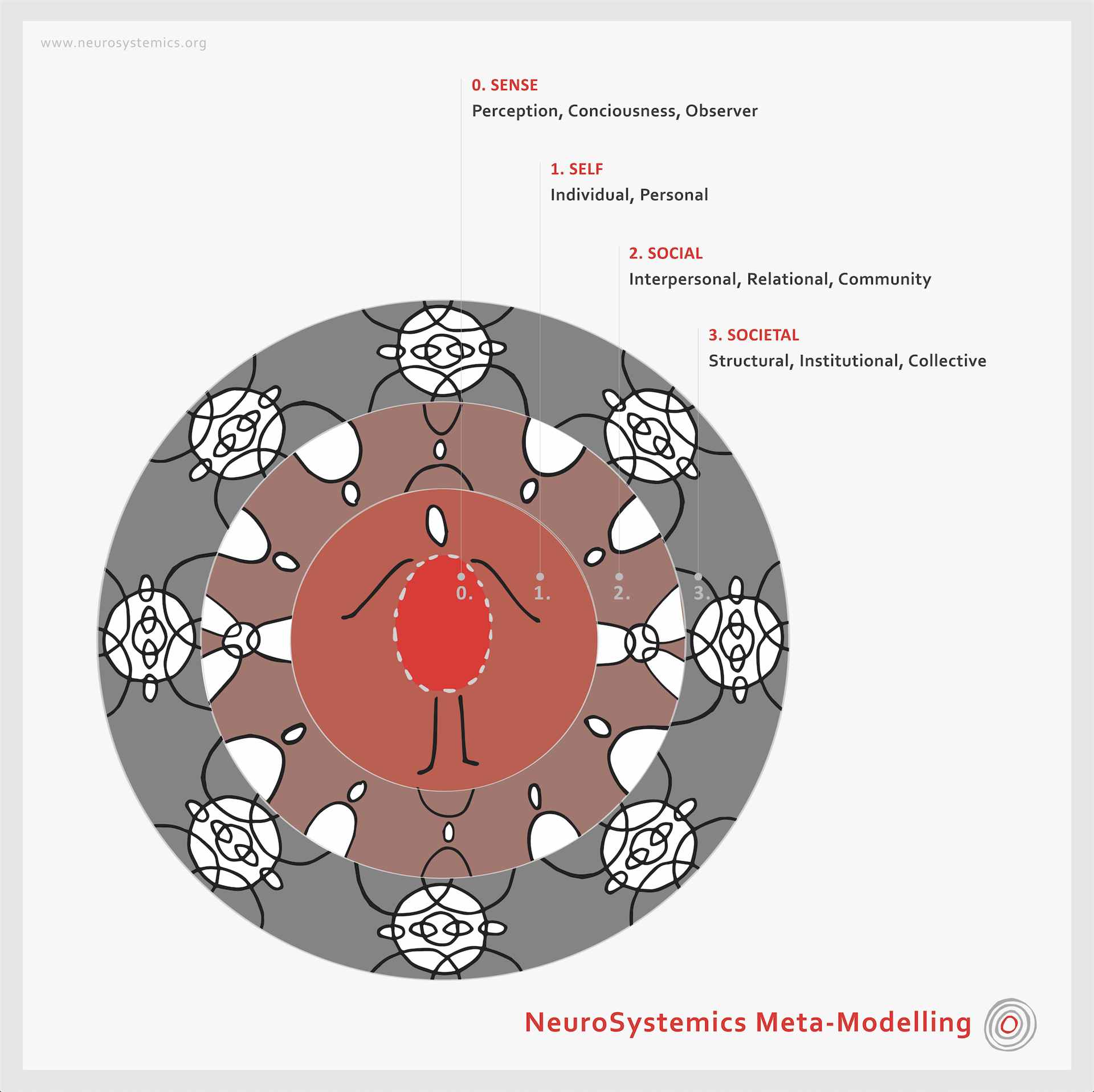

NeuroSystemics is a clinical practice that can be applied in four settings: (i) mental training, (ii) individual therapy, (iii) group therapy, and (iv) community processes. They each correspond to the concentric circles of (i) sense, (ii) self, (iii) social and (iv) societal, respectively, in the following diagram:

In whichever setting, we attempt to engage with all the parts of that system as well as the system as a whole. Biology and affect, as holonic fractals, can be both parts and wholes, depending on the breadth of attentional focus and practice setting.

For example, in mindfulness practice, the emerging sensate networks of the in-out movement of the breath can be experienced as a dynamic wholeness with many interacting features. When attention is broadened, the spectrum of awareness may include. A sense of the whole body, in which the sensate rhythms of the breath would only be a part. The key here is to provide a firm foundation for understanding the interdependence of human experience, whereby any efforts towards differentiation necessarily imply consideration for integration and contextualization.

Baring this fundamental principle of complex functioning in mind, it is of great benefit to explore mono-developmental trajectories, where a single dimension of human experience such as physiology, affect or cognition is cultivated. The next section describes the way NeuroSystemics understands resiliency and empowerment through a differentiated lens of biology and affect.

Biological development

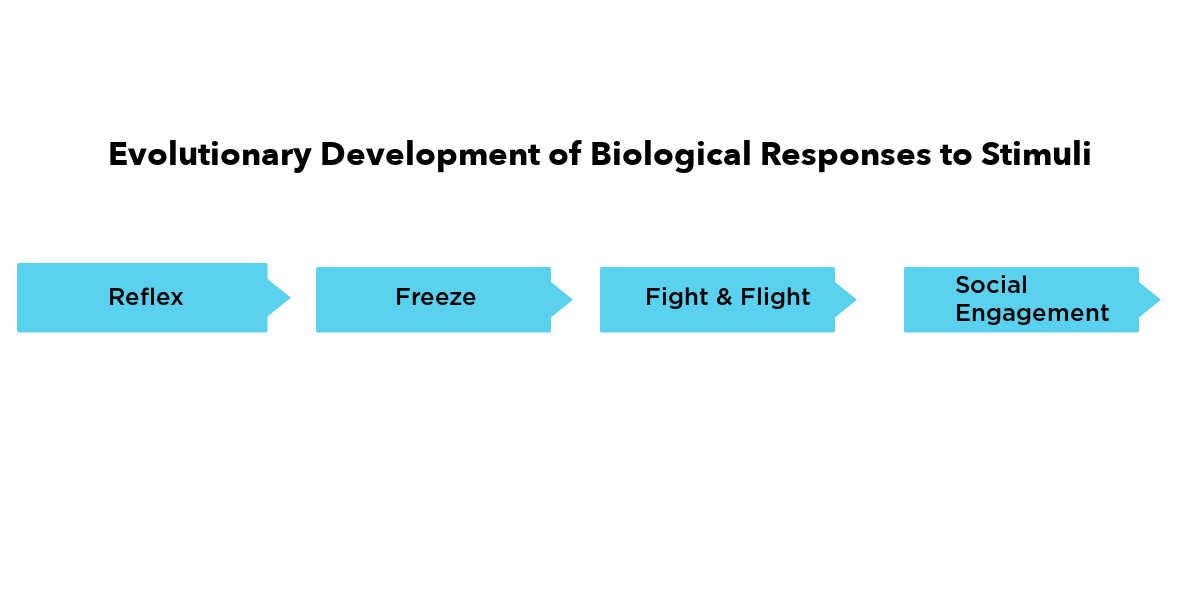

When considering the possibilities of somatic cultivation, development, and training, it is helpful to refer back to our evolutionary process. Porges’ polyvagal theory describes a fairly linear direction in terms of physiological responses to stimuli from reflexes to social engagement. See this diagram of it.

Reflexes are the most primal physiological responses to the environment. They arise based on sensory contact of comfort and discomfort. Freeze, a shutting-down of major physiological systems, was already a more elaborate form of response to reflexes. It increased the probabilities of survival by “playing possum” and escaping one’s prey after they become disinterested. Fight-and-flight offers more opportunities for a differentiated response to threat and social engagement and is the culmination of a multi-million-year process of refinement. This last system arises out of feeling a sense of safety and promotes curiosity, playfulness, and enjoyment.

A first important therapeutic goal, based on this evolutionary framework, NeuroSystemics uses elaborate maps, therapeutic conditions and interventions to support the emergence of social engagement. Porges’ neurophysiological findings have demonstrated that the freeze-flight-fight and social engagement systems are aroused in inverse proportions.

One key practice to sustain a socially engaged nervous system state is to encourage the clients’ self-organizing impulses. These impulses, also known as

Chanda in Buddhist meditative texts and

Eros in Freudian meta-psychology, are generative organismic drives towards health, clarity and well-being. Supporting them implies sensing into the clients’ system as a whole, while simultaneously differentiating its parts to identify signs of arousal and deactivation: physiology (prosody, facial expressions, agitation, etc) and free-associative process, their affective variations, their bodily movements as well as their quality of presence in relation to the therapist (i.e. trust, vulnerability, appreciation).

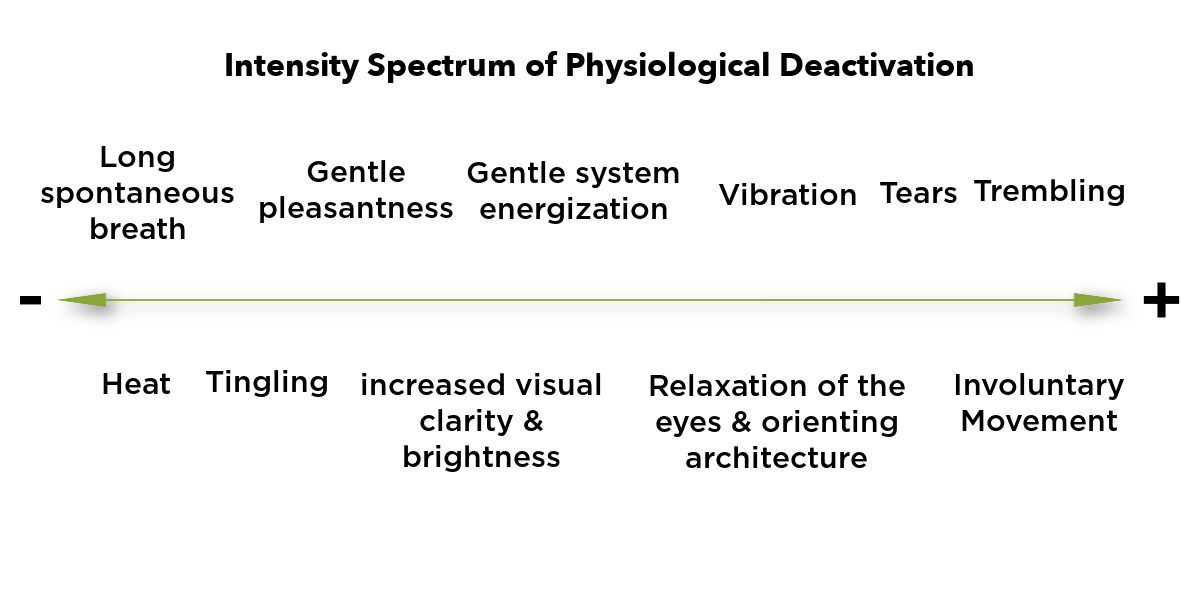

Intensity spectrum of physiological deactivation

When we work with the autonomic nervous system, we are walking a fine line between increasing the nervous system's backlog, or reducing it. Our aim in Neurosystemics (somatic-centered therapy) is to reduce it by reaching gentle and enjoyable thresholds (the edge of our client's window of tolerance) and then deactivating the system. You can assess the intensity of the threshold reach by identifying the symptoms of deactivation, which are on that spectrum above: the most subtle and easeful deactivation symptoms are spontaneous breaths and soft heat, and the most intense are involuntary movements and shaking. While some of the more extreme symptoms may sometimes be inevitable in our work, in NeuroSystemics we aim to have easeful and smooth deactivations so that our clients can stay oriented to the here-and-now and have better chances of integrating this somatic process easily in their daily life.

All these factors (and others) will provide valuable indicators to assess whether the physiological coherence and synchronicity are growing or diminishing. Therapists then adapt their interventions to provide more or less containment to shepherd a higher level of physiological resiliency.

Complexity science has also provided a number of essential findings to support us in biological maturation. It explains that increasing levels of organization emerge from phase transitions which occur by reaching thresholds at far-from-equilibrium states. Human physiology has non-linear patterns whereby rhythmic oscillatory movements between equilibrium (homeostasis) and far-from-equilibrium states (morphogenesis) enable increasing levels of metastability.

In terms of practice, this means that we will want to support our clients, in a gentle, progressive, and positively-valenced manner, to come into contact with physiological states which feel out of balance. By listening to the multi-faceted impulses (physiological, affective and cognitive), a cushion of resource and ease can help to soften, contain and eventually convert previously overwhelming sympathetic charge into regulating and organizing patterns of coherence and synchronicity.

In summary, the two directions proposed by NeuroSystemics to encourage biological maturation is to conceive of skillful means to sustain our clients’ social engagement nervous system states, as well as to ground their physiology in gentle and progressively increasing rhythmic oscillatory movements between homeostatic and morphogenetic states. These will enable greater physiological resiliency, somatic embodiment as can be indicated by heart-rate variability.